Destruction and Creativity: ISIS, Artefacts and Art in the Middle East

Widespread outrage. National and international mourning. History redefined. These are the terms used to describe the destruction caused by Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shams (ISIS) who, since bursting into the international limelight by capturing Mosul in June 2014, have made acts of iconoclasm – the purposeful destruction and defacement of art and artefacts – key to their strategy of inducing fear, exerting power, and garnering support. The Temple of Baalshamin and the funeral towers in Palmyra, which both date back almost 2,000 years, are the latest targets in ISIS’s increasingly widespread and rapidly growing attack on history that now includes ancient sites in Nimrud, Hatra and Mosul in Iraq and Aleppo and Palmyra in Syria. These acts are constantly discussed in terms of Islamic fundamentalism and the ultimate loss and waste of human history– but is there more to iconoclasm than these reductionist portrayals?

ISIS, Iconoclasm and the Media

Since June 2014, ISIS’s iconoclastic rampages have become regular features of news articles and broadcasts. But beyond this current media frenzy is a legacy of mediatisation of such iconoclasm. Another infamous example that garnered similar global outrage and attention was the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001. The Financial Times has also created a portfolio of recent iconoclasm, entitled ‘Artefacts Under Attack’, on their website covering Islamic extremist groups that have destroyed objects in Iraq, Syria, Mali, Egypt, Afghanistan and Libya. This mediatisation of the iconoclasm performed by ISIS and other Islamist groups has created an association that presents such destruction as inextricably linked to Islam, and vice versa. The lack of media coverage of any other form of iconoclasm, or any other brand of perpetrator or motive other than Islamic fundamentalism, further solidifies this association.

This presentation by the media misrepresents iconoclasm – it is not a purely Islamic, or religious, practice and it is not a new phenomenon. In fact, iconoclasm can be found in cultures across the world and throughout all time periods – even in the UK. The pervasiveness of iconoclasm as a practice lies in its signification: It is a symbolic visualisation of a challenge to or change of power. This was captured brilliantly in the Tate’s exhibition Art Under Attack (2013–2014), which showed the remains or documentation of iconoclastic acts in Britain or by the British, ranging from the 16th Century to today. The show included religiously inspired attacks on objects, such as during the Protestant Reformation; politically and socially motivated attacks such as those conducted by British Suffragettes; and contemporary iconoclastic acts that sought to challenge post-modern aesthetics.

Creativity Born from Destruction – Contemporary Responses to Iconoclasm

Whilst iconoclasm is understandably distressing and should be discouraged and prevented wherever possible, there is another side to such destruction. As renowned visual culture theorist W.J.T. Mitchell explains: “Iconoclasm is more than just the destruction of images; it is a ‘creative destruction’.” By this, Mitchell is discussing the layers of meaning that are added to an object each time it is modified in any way – even if that modification is destructive. But there is yet more creativity to be found in the inspirational qualities of iconoclastic practice – after declaring outrage and even experiencing a phase of mourning, people have an overwhelming desire to produce material responses. Artists are drawn to the destructive practices of iconoclasm both in terms of materiality and conceptuality. For some, their creativity is an act of memory, preservation and positive production; an act of nostalgia, mourning and a filling of a void; or an act of determination and defiance in the face of hostility and threat: more often than not it is a combination of all three and more besides.

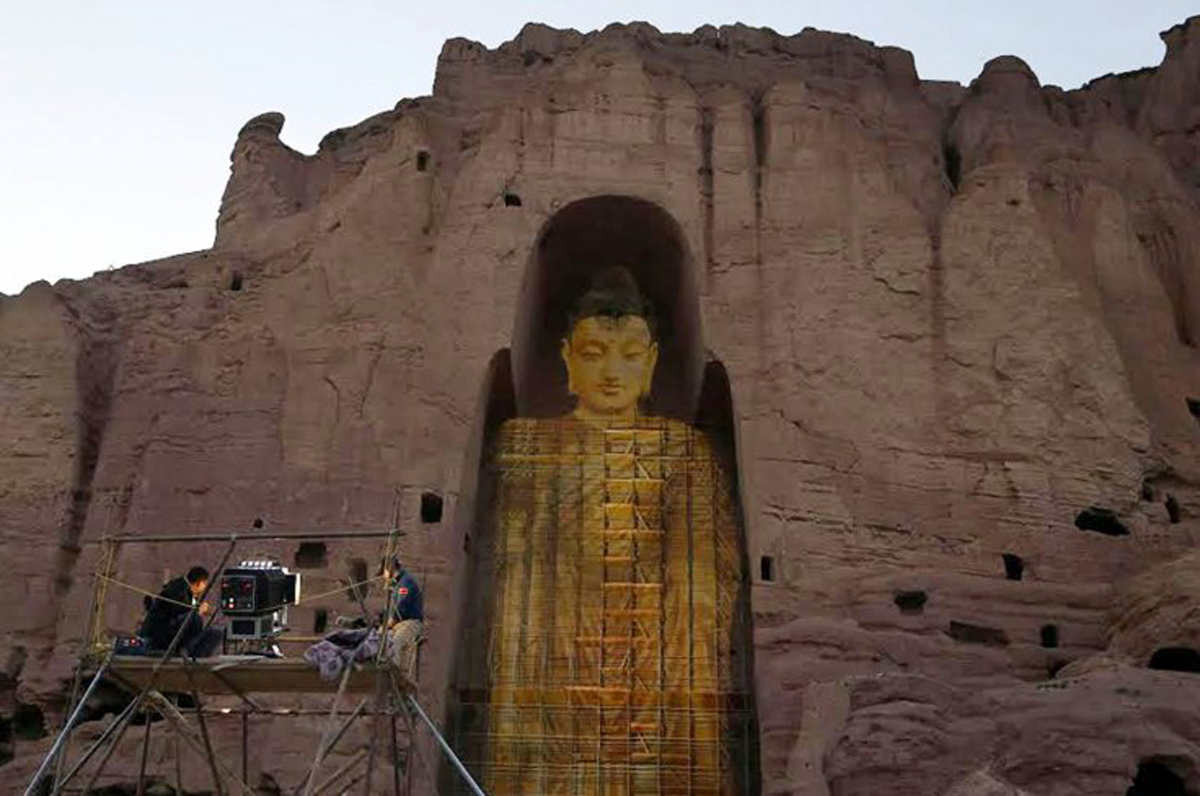

Creative responses to destruction in the Middle East abound in the art world and, in particular, new technologies are rapidly becoming integral to such reflections. One of the most recent examples, which was well documented in the media, is the Bamiyan Buddha hologram created by Chinese couple Janson Yu and Liyan Hu in June 2015. The pair created and self-funded a projector at a reported cost of $120,000, travelled to Bamiyan to show the hologram, and then gifted the device to the Afghani government for future audiences to enjoy. This project went some way to restoring cultural patrimony and filling the physical, emotional and symbolic void left by the Taliban’s destruction.

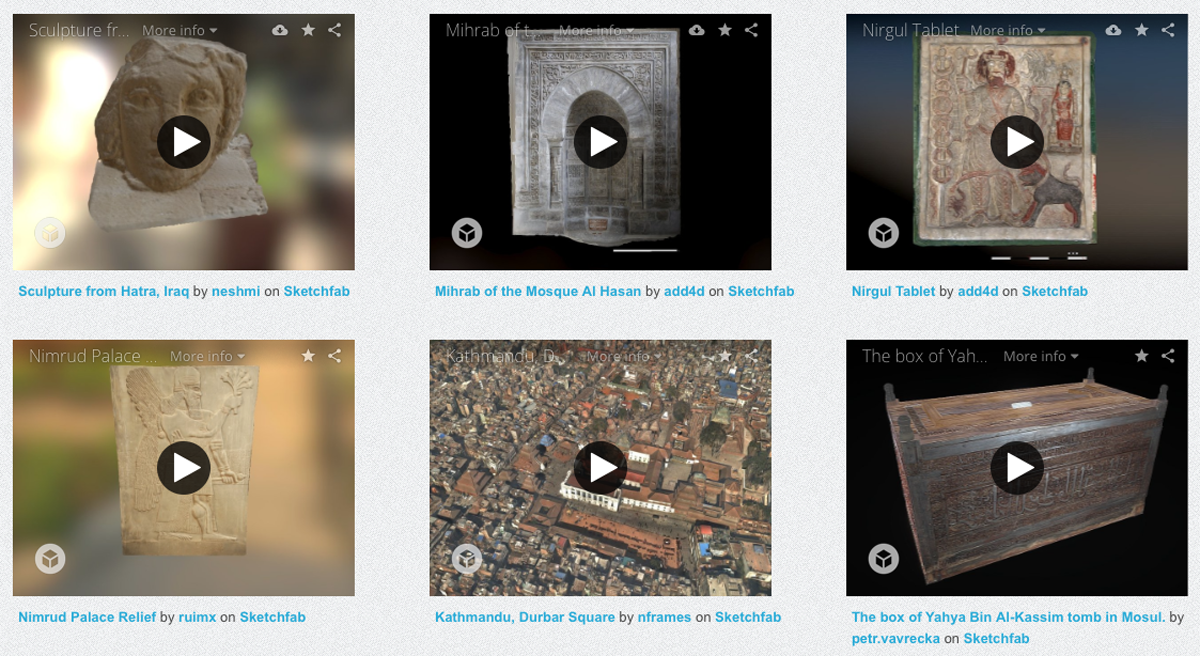

Another example is Project Mosul who, in response to the iconoclastic acts of ISIS, are using virtual 3D modelling to recreate artefacts destroyed in Syria and Iraq. Project Mosul, a volunteer initiative based in 10 different European cities, is using crowd-funded images to create virtual 3D models of destroyed Iraqi artefacts in the hope of creating an online museum accessible to all. This method of recreation has also been taken up by The Institute for Digital Archaeology, a joint venture between Harvard and Oxford Universities, which is sending thousands of 3D digital cameras to parts of the Middle East where buildings and artefacts are considered ‘high-risk’ so that locals can capture their visual details. Such efforts bring back a sense of agency to those whose heritage is being destroyed and helps keep the objects and their meanings alive.

Iranian-born artist Morehshin Allahyari is also utilising new technologies, choosing to reproduce artefacts destroyed by ISIS through 3D printing. Her project Material Speculation: ISIS (2015) has involved extensive meticulous research into the destroyed objects, which she found to be heavily under-documented, and then producing the resin copies based on the information she uncovered. Her work is particularly interesting due to the combination of the virtual and the physical – each of her 3D printed sculptures holds a USB drive and memory card containing images, maps, PDF files, and videos from her research into the object. For Allahyari’s replicas it is almost as if the objects themselves have a memory built in and her work is a clear response to a widely-held desire to make historical objects somehow ‘future proof’ – to remove the possibility for forces such as ISIS to wipe out historical narratives and differing views, consolidating their power.

These examples of contemporary art inspired by iconoclastic acts show how iconoclasm is part of a process of visual development. Beyond the horrors of destruction, artistic reflection on iconoclasm is developing our understanding of what art is, its purpose, and how it can ultimately further our understanding of collective memory, history and society. In this way, artists are performing important roles as archivists, mediators, and producers in the contentious act of iconoclasm. Innovative technologies, such as 3D printing, holograms and 3D virtual imagery are increasingly featured in contemporary art and bring new propositions and capabilities in the reinterpretation of destroyed artefacts and images. Whilst the future of historic Middle Eastern images and artefacts is uncertain, and new acts of destruction can be found in the news on an almost daily basis, it can be of some comfort to know that iconoclasm is inspiring new creativity and understanding for our contemporary world.

This blog post is based on a wider research project conducted for Aimee’s MA on Contemporary Art of the Middle East at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

Previous Mosaic Rooms events relevant to this subject include: Recorded Lecture: My House in Damascus

Aimee Dawson is a London-based writer and blogger on contemporary art from the Middle East and North Africa. She studied Arabic and Middle East Studies at the University of Exeter and spent a year living and studying in Cairo and Fez. She was the writer-in-residence for Shubbak Festival 2015, is a guest blogger for Nour Festival of Arts 2015, and is the Editorial Assistant at Ibraaz.org. She has recently completed her Masters in Contemporary Art and Art Theory of Asia and Africa at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.