Engagements with the photographic archive – Bruno Boudjelal in conversation with Katarzyna Falecka

Bruno Boudjelal is a photographer and member of the VU photography agency in Paris. Born in France and of Algerian extraction, Boudjelal’s work has focused on his complex relationship with Algeria. Through photography, he ceaselessly investigates his own identity and memory, triggering larger questions surrounding the contested history of French colonialism in Algeria. Katarzyna Falecka curated an event about archival photography and contested archives for The Mosaic Rooms in November 2016, as part of the programme of events for The Mosaic Rooms’ exhibition What Language Do You Speak Stranger? by French-Algerian artist Katia Kameli. Bruno Boudjelal was originally programmed to speak but was unable to attend. In this interview for The Mosaic Rooms he speaks to Katarzyna Falecka about his practice.

You first travelled to Algeria in 1993, in the early years of the civil war. What were your motivations for this journey?

I grew up in France with the sense of a double identity: my mother is French and my father arrived to France in 1954, at the beginning of the Algerian War of Independence. Often, he would hide his true heritage from friends and claim to be of Italian descent. In 1993, I decided to find out who I really was and meet my Algerian family. But immediately after I landed in Algiers, I realised how terrible the political situation was. The violence and fear were unimaginable. I was arrested numerous times and was told to go back to France. Nevertheless, I decided to continue my journey and travel to the area of Sétif where my father’s relatives lived. However, I took some time to travel around the country first, despite the danger. I took a certain ‘detour’ you could say. I needed this time to gain some distance to what was an already highly emotional experience.

Two days before my departure to Algeria, a friend gave me a simple analogue camera. But I was not even interested in photography at the time. However, the camera helped me to keep a distance from the chaos that was evolving around me. I continued to photograph and later became a member of the VU photography agency in Paris.

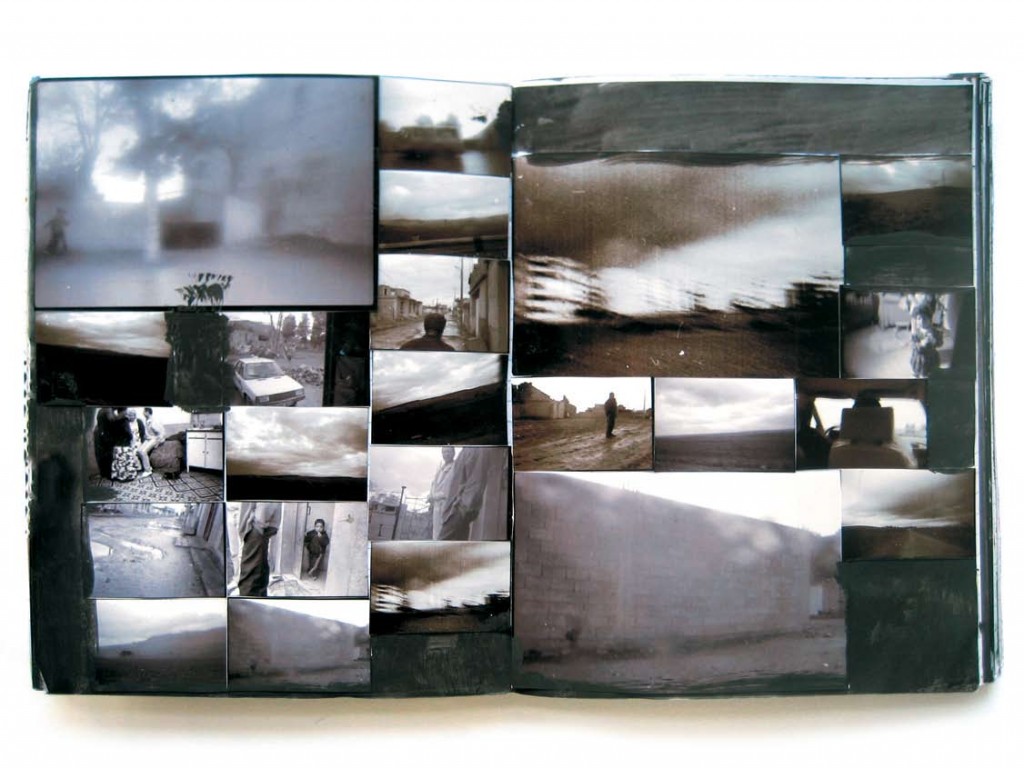

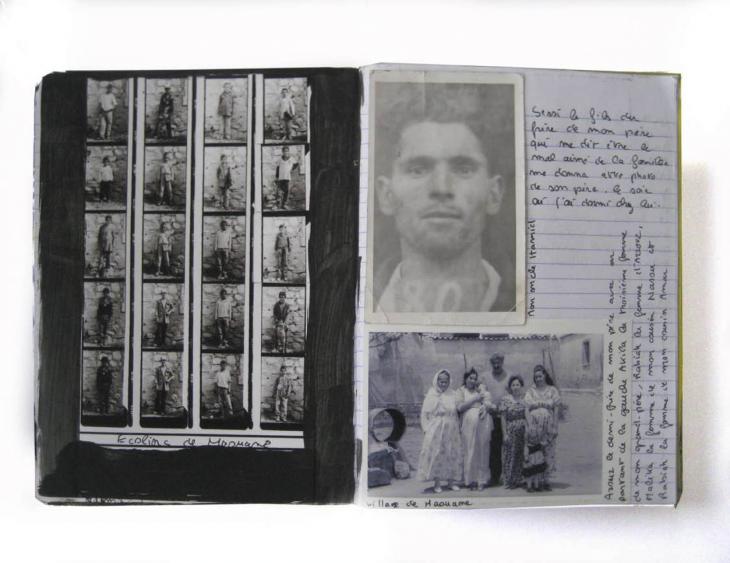

Archival images have played an important role for you in the process of understanding your own heritage. This is made particularly visible in your series Scrapbooks (2009), a travel diary which includes your birth certificate, photographs of your Algerian family, your own childhood photographs and the images you took in Algeria in the 1990s and 2000s. In what ways have family photographs helped you understand your own identity and how would you define your relationship to this ‘archive’?

It is difficult to get hold of photographs of family members predating 1962 when Algeria gained its independence from France. One of my aunts who lives in Sétif gave me some photographs when I first visited. She also asked me to send photographs of my life in France to her. We continue this exchange until today.

For example, I have two photographs of my grandfather Amar, as well as his birth certificate. The images were included in his identity cards, issued by the French for surveillance purposes. Another photograph is a mugshot showing my uncle Hamid who was a member of the National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria. He was imprisoned, tortured and killed by the French army under the suspicion that he delivered food to the partisan camps. The mugshot shows him with a board and the number 80 written on it. However, the family memory is blurred and thus there are many uncertainties surrounding the photograph too. I was not able to clarify my uncle’s role in the FLN. He is simply hailed as a great ‘moudjahid’ (fighter) by my family.

When my aunt dies, the memory will die with her. Other family members are not too concerned with the past. This is symptomatic of a general amnesia about the war in Algeria. For me, finding out where I come from and who I am was crucial. But there are many people in the country and abroad who do not yet have this knowledge.

In fact, I am going to show Scrapbooks for the first time in Bangladesh this year. I have never shown them before, despite numerous offers. I think that they are in some way too personal to be shown in France or in Algeria, where memory of the shared past is still highly contested. My story is a small one, but perhaps it can acquire a more universal meaning for an audience in Bangladesh.

One of the diary entries published in your photobook Disquiet Days, describes the efforts to find your family after arriving in Algeria. But this was no easy task and you quote an official who asked ‘why do you think we’d know this family? We’re not machines. The records from the French times aren’t here’. He referred to the fact that following independence, records relating to colonised Algeria were transported to France. As a consequence, Algerians lost access to their own recent history. In what ways do you think has this influenced the ways in which history and memory have been mediated in Algeria since 1962?

Algerians need this access in order to counter the overwhelming amnesia which rooted itself in the collective consciousness. This can only be cured through working closely with archives, photographs, testimonies and other documents. However, there is little emphasis on building collections or archiving in Algeria today. This is an explicit political choice of the government who benefits from peoples’ limited awareness of the historical developments of their country.

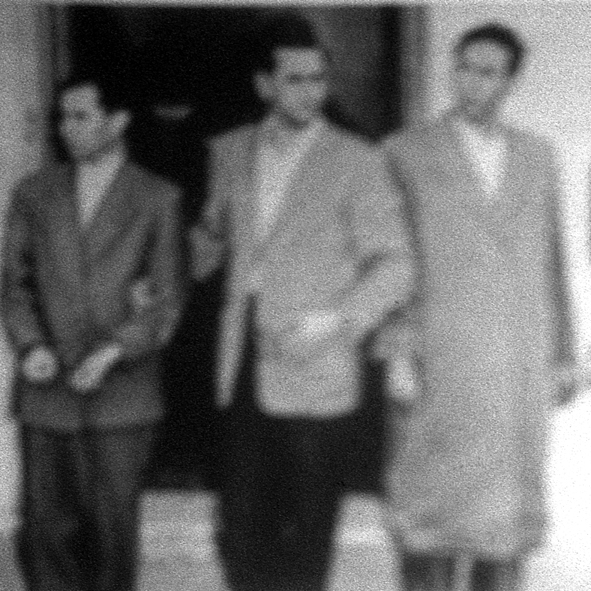

Your engagements with archival photography move beyond the family album. For a series devoted to Frantz Fanon, you re-photographed an iconic image of the FLN leaders Mohammed Khider, Mustafa Lacheraf, Hocine Ait Ahmed, Mohamed Boudiaf and Ahmed Ben Bella following their arrest in 1956. You re-photographed it in a way that both Khider and Ben Bella were cut out from the image. The photograph is also entirely blurred which resonates with the use of blur throughout your practice. Can this image be seen as a comment on post-independence Algeria?

The photograph is part of the Frantz Fanon series which I started in 2009. Fanon was a Martinique born French-Algerian psychiatrist, philosopher, member of the FLN and writer whose work influenced decolonial thinking. He lived for years in Algeria, working as a psychiatrist in a hospital in Blida. I felt it was important to retrace his legacy at a point when the country was approaching its fiftieth anniversary of independence.

Working on the series was a challenge. For example, I never managed to enter the hospital where Fanon had worked. A friend who accompanied me there was arrested and interrogated by the police. Even when we visited Fanon’s mausoleum, 80km south of Annaba, military checkpoints and constant surveillance made shooting photographs difficult. Photography is still considered with great mistrust in Algeria. I found it easiest to photograph on the go, constantly moving, never standing still.

I find that there is a persisting difficulty in making works about the past in Algeria. The cropped and blurred image speaks about this too. All of the FLN leaders have now died but they have been absent from the history of the country for a while now. Since independence, a constant confiscation of memory and history has been taking place. What Algerians are left with now is a State sanctioned narrative and it is almost impossible to counter or criticise it openly. My alterations on the iconic photograph embody these manipulations and shifts. Today, few young Algerians know who Ait Ahmed was. Ben Bella, the first Algerian president, lasted for three years before being overthrown in a military coup in 1965. These people are no longer present in official memory. One of the things I regret today is not taking portrait photographs of Ait Ahmed who was a friend and who asked me to do this a while ago…

Bruno Boudjelal, Restless Days: Algeria from East to West, 2001-2003. © Bruno Boudjelal and Agence VU

The blur has been a defining feature of your practice. During the civil war it was an outcome of the danger and the actual inability to photograph in public spaces. However, you have kept the blur even after the conflict came to an end in 2002. What is the value of blur in representing Algeria today?

When I first visited Algeria, I had no specific agenda. I thought it would be my only visit to the country. When I came back some years later, I made the conscious decision to keep photographing but always used simple cameras in order not to be recognised as a photographer. I realised that you are fine in Algeria if you keep moving and act as if you knew your way around. The minute you stop, you get into trouble. Of course, even if blur was not a conscious aesthetic choice at first, it still carries a lot of meaning. To some extent, it registers the invisible, that which is suppressed and occluded. I have not been able to find another way to photograph Algeria nor to produce a focused image. Perhaps the blur speaks of my own failure to frame Algeria through the camera lens.

Katarzyna Falecka is studying for her doctorate at University College London. Her doctoral research looks at the ways in which photographers and artists have engaged with photographic archives from colonial Algeria, with a focus on visualisations of conflict produced during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62). She was involved in the production of the ‘The End of the 20th Century. The Best is Yet to Come’ exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum, Berlin in 2013, where she assisted Professor Eugen Blume. She has worked as researcher for the Jewish Museum London and is currently completing a Secondment at Tate.