Rachel Dedman: My Home Is An Archive 3

I am rifling through a stack of ancient newspapers one day, when I receive a call. The magazine I am reading – Burda – is typical of the kind scattered across Lemontree House, a German fashion magazine from the 1960s. Inside, shiny-haired ladies with pointed shoes smile in knitted bathing suits and longline cardigans over kicky A-line skirts. Such periodicals come with sewing patterns so women might make the clothes they see within. To save space, multiple patterns are layered together on one sheet, numbered and coloured so the reader can distinguish between them. These featherlight papers resemble beautiful maps of strange waters, utterly unnavigable.

The woman on the phone is Christine Zacharias, who works at ALBA – the Academie Libanaise de Beaux Arts – to whom I had submitted a message online enquiring about Georges Guverdjinian, having discovered he was both a student and professor there. The school’s website only had a standardised online form to submit queries, and I hadn’t expected a reply. Christine had seen it, however, and got in touch – she and her husband had been taught by Guv, and her mother-in-law knew him too; she even had one of his aquarelles on her wall. Above all, Christine recommended I speak to Harout Torossian, an artist and good friend of Guv – they taught together at ALBA.

On a hot day about a week later, I meet Harout in ALBA’s outdoor café, where we sit and talk in the breezeless shade. Harout is an artist’s artist. All white hair, jaunty hat and gentlemanly French demeanour; he kisses my hand when we are introduced. He speaks no English, nor Arabic, issuing from an era where an Armenian-French hybrid was all you needed in Beirut; for many it still is, though most young people now speak English too.

At 80 years old, Harout is still a charmer, and a very successful painter; I had recognised his name from posters advertising a big retrospective exhibition a few months previously. He laughs in cheeky conspiratorial cackles. Based between Lebanon and Paris, when he is in Beirut he keeps a studio and flat in Bourj Hammoud, where he is currently painting a huge two-metre canvas of Adam and Eve, a private commission. The nude, the body – these are Torossian’s real loves. He makes me a gift of a recent monograph, a blue book filled with essays from other artists and friends, images of his paintings, and pages of photographs collaged together – of Harout and his pals, his family, other art bigwigs, and (he points out with great pride) the President of Lebanon. His paintings are gorgeous, constructing the body from a combination of brushstroke and the inherent texture of paint; academic, but with something vital captured too.

I ask him what it was like to be an artist in Beirut in the twentieth century. Before the civil war, he tells me, it was calm. There was a market for art, though not a great one, but if you had an exhibition, you would sell. Once the war started, many artists travelled abroad, emigrating to Europe. Harout stayed, and describes a strange equilibrium to his experience of the conflict – if there was a bomb here, there was a bomb there – referring to the split down Beirut’s Green Line between the city’s East and West. He confirms it was dangerous, every walk in the street might meet with an explosion; a remnant of the conflict that continues today, as bombs still rattle Dahiya, Beirut’s Southern suburbs, in the week we meet.

Harout trained as an artist in France initially, before returning to Lebanon to join ALBA in the third year they accepted students; Georges Guv was among the very first generation at the school. Harout confirms a few physical details about Guv I had gathered from the one small photograph I’d seen. Of mid-height, with brown-grey hair and a clean-shaven chin, Harout tells me Guv was a principled man, always polite, “and very loyal to his wife, extremely loyal”. Guv’s entry in the Index of Painters suggests he did not spend much time in the social scene that swirled around ALBA, an artist without any of the arrogance or pride a celebrated painter might have had then. As well as teaching undergraduates at ALBA in an academic manner (drawing, charcoal, oil painting), he also taught art to younger children, in an Armenian school whose name Harout could not recall. From the Index I had also learned that Guv served in the Lebanese Association for Tobbaconists, as “fonctionnaire a la Regie Libanaise des Tabacs et Tombacs” and ran a papeterie alongside his ALBA teaching.

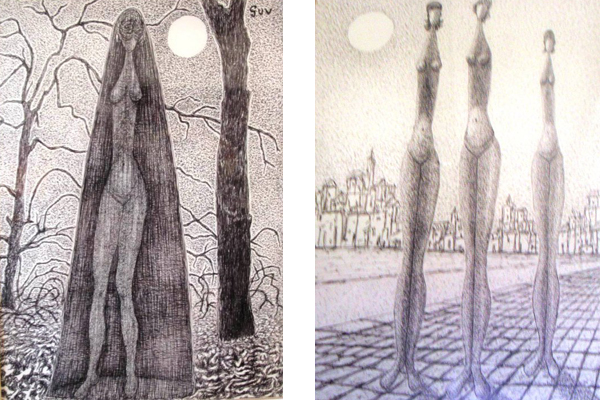

Georges Guv, it seems, was in many ways an ordinary man, but one with an extraordinary depth of feeling. The person who left his tobacco post and stationery shop, who came home to his wife and children each night, was deeply affected by the problems of the world. Harout tells me that Guv felt keenly the suffering of humanity; and his painted forms were lively until catastrophe struck, when he would abandon colour. Harout describes Guv’s paintings from the civil war: using greys and dark tones, Guv enclosed his canvasses within a thin skein, stuck to the still-wet paint, this sticky shield closed a curtain on their darkness. These resonate with the drawings I’d seen, the spindly, armless forms floating in monochrome landscape, staring at something beyond the frame; imbued with a loneliness or melancholy.

This also chimed with what I had been gathering from Arlette, who was recounting in our email correspondence the full histories of her family. She described the difficult journeys her grandparents (Guv’s mother and father) undertook to Lebanon. In the great massacre of Armenians at Izmir, the family all miraculously survived, but were split from one another. The children – Guv, aged 3, and his sister, aged 6 – found themselves bundled onto a boat bound for a Greek island, while their mother was placed on a ship to Beirut. Their father was captured by the Turks, a lucky fate since the vast majority were slaughtered, but it was two years before he could escape and make his way to Lebanon. Here, with the help of his wife and an uncle who lived in Martyrs Square, they located the children, still living in Greece, and brought them to the city to join them.

The story of Guv’s journey to Beirut resonated powerfully with the images I had seen of his work. Having to flee a flaming city to Greece, aged only three, with no-one but his six year-old sister, must have been a traumatic and terrifying experience. Living there without either parent for two years, perhaps as isolated by language as by the unknown fate of his family, the lack-limbed female figures in his ambiguous drawings take on new potency. One can’t help but understand reports of his heightened compassion and sensitivity to suffering in terms of his harrowing early years, and imagine the amputated women as lingering emblem of separation from his mother. Witnessing the horrors of the civil war in Lebanon, decades later, must have been particularly haunting.

A generation on, Guv’s daughter Arlette remembers a peaceful and prosperous childhood growing up in Beirut, first in Geitawi, then in Gemmayze, a neighbourhood nearby. The children encountered no racism as a result of their Armenian heritage, though they were teased for their sub-standard Arabic, speaking nothing but French at home. Guv had exhibitions, television interviews, articles, and travelled all over the world. In 1975, however, the civil war changed a great deal. Arlette tells me that by this time she was living in New Jdeideh, a district outside Beirut, to the North, with two small children of her own. All of the close family who lived in dangerous zones in the city would come to stay with them to escape gunfire and bombings. They lived precariously, with little water and even less electricity, taking shelter with their children in the dirty basement of the apartment block, full of rats. Around a year into the war, a bomb fell onto their building, destroying the majority. The family had been out at the time, but this close call was the final straw for Arlette, who then hurriedly moved her family to Paris, where her brother Francois had relocated his young family just a few months before. Her parents, Guv and Marie-Jeanne, would stay in Beirut another 6 years, moving to Paris in 1982. Under such circumstances, one can imagine the lack of need, if not opportunity, to sell one’s home. After luggage is packed the house is shut up, all but the essentials left within, locked with fervent promises to return one day.