Q&A with Dr Caroline Goodson, Senior Lecturer in History, Classics and Archaeology at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Caroline will be presenting her lecture With A Seamstress Tape And A Smile at The Mosaic Rooms 31 July. RSVP to reserve your place at rsvp@mosaicrooms.org.

Q1/ In addition to your academic teaching in history archaeology, you have also excavated and carried out field work in Morocco, Algeria and Italy. Can you tell us a bit about how/why you became interested in Archaeology – particularly in your main area of research, medieval cities?

I first went to Rome in 1995 and as I wandered around the city, I kept finding myself going down into basements of churches, or restaurants, to see the earliest parts of the buildings. I became curious about how we knew which part of a basement was a Roman house, which part was a medieval basilica—I found myself doing the archaeology of architecture, and then I decided to study it seriously, going to Columbia University for a PhD, and studying archaeological methodologies at an institute in Italy. Periods of major change fascinate me, so I am very interested in the what the archaeology of the early middle ages tells us about the end of the Roman Empire and the beginnings of small, dynamic political structures, like the papal state in Italy or the Islamic emirates of North Africa. I wrote a book on Rome in the early middle ages, and my core research examines medieval cities as places of presentation, where political and religious ideals were communicated to those who were affected by them. I like thinking about buildings as tools of expression, and so I look at monumental architecture, like palaces, churches or mosques, as well as the houses of the people who were meant to be impressed by the monuments. Archaeology permits me to reconstruct the built environment, in a sense, both from most prestigious to the lower status.

Q2/ During your upcoming talk at The Mosaic Rooms you will be introducing us to the work of Victorian-period archaeologist Esther Van Deman, as well as other pioneering women archaeologists who worked in Italy and North Africa at that time. Can you briefly tell us why these women we so interesting/important?

Firstly, the history of archaeology is predominantly a story of men, most often told by men. The exhibition of these photographs provides an opportunity to remember that many major contributions to our understanding of the past and the techniques we use as archaeologists were made by women. Esther Van Deman was as well-educated as any upper-class American man, and she set out first to Rome then to North Africa to pursue her research in Classics. Her interests lay in recovering the techniques of construction of major pieces of Roman engineering and technology, and she pursued this inquiry looking both at single monuments which were under excavation or recently revealed and looking very broadly at how Romans built buildings. She developed methods of recording and documenting that were scientifically rigorous and show a real analytical mind with a rich historical perspective gained by her classics training. Secondly, Van Deman and other archaeologists of this period travelled widely and lived exotic and fascinating lives, through world wars and going to very remote places. These photographs shed some light on the enormous distances she travelled with her camera and her measuring equipment, in a Mediterranean world that was very different from our own.

Q3/ Some of Esther Van Deman’s photographs are on show at our current exhibition My Sister Who Travels. Can you pick a couple of your favourite images and tell us a bit about what they depict/ why you like them?

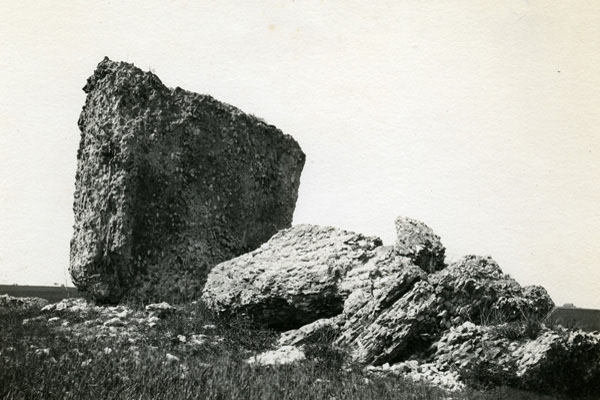

30 Guyotville, Algeria, dolmen, 1913 VD_4427 – [Site now called Ain Benian] This is such a classic archaeologist’s photo: with a folding rule and a digging hoe used as the auxiliary measure. It’s a prehistoric rock structure, put up as tomb monuments (probably). This is one of several dolmen in a necropolis of Beni Messous which was excavated in the 1860s and again in the 1920s, as colonial French built vineyards in the hills north of Algiers.

10 Herdoniae, Italy, remains of a Roman bridge called Ponte Rotto, across the river Carapelle on the Via Traiana, no date VD_2012 – This site was of major importance in the Punic Wars and classicists were attracted to it because of its connection with Hannibal and some legendary battles. The ruins of the Roman city were only excavated after World War II, so Van Deman must have gone down following the line of the Via Traiana – a major road repaved in the second century to facilitate traffic of people and goods across northern Puglia to the port of Brindisi. The photo shows the aggregate concrete core of what was a brick-faced concrete. The external facing of the concrete has been ripped off and reused, probably in the middle ages, and all that is left is a collapsed concrete, folded on top of itself.