The Revolution within the Revolution: Art and Syria Today

Read the latest post from our guest blogger Aimee Dawson, for a broad overview and initial insight for those wanting to begin to know about art in Syria today:

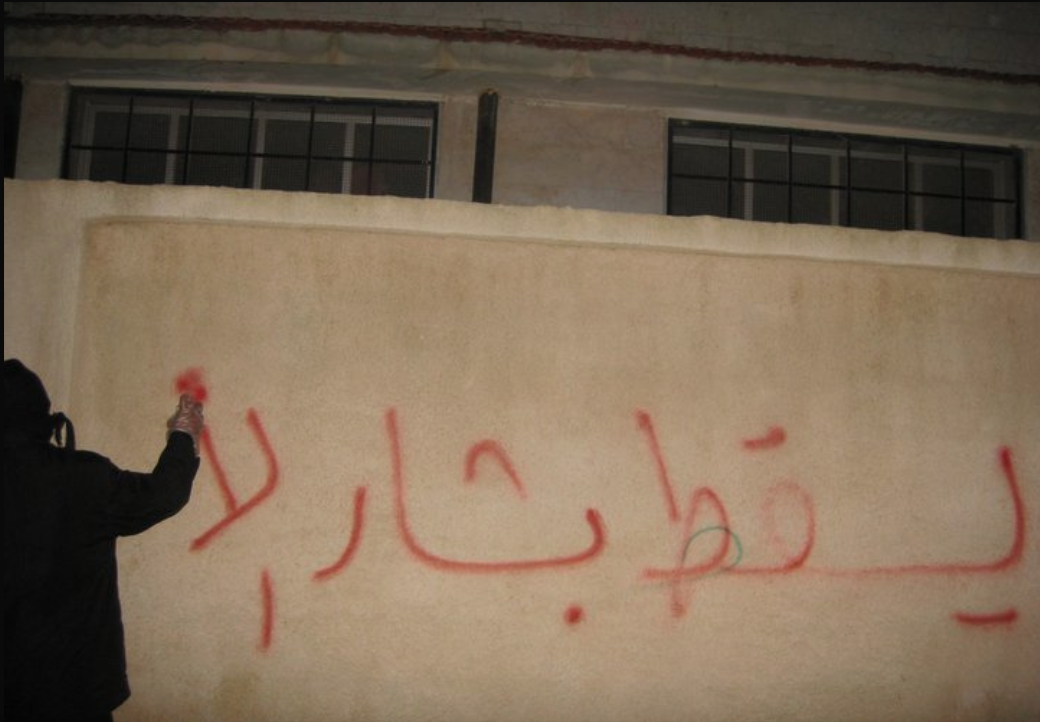

In 2011, a small piece of graffiti demanding the fall of the Syrian regime instigated a vicious crackdown by the government upon its young perpetrators. This graffiti was arguably one of the catalysts that led to the Syrian Revolution, which has since deteriorated into the now four-year-long civil war. It is somewhat fitting then that today, the cultural and artistic responses in the war-torn country have been described as the only positive development of the conflict. Despite the widespread devastation – which has seen over 230,000 people killed, more than 4 million fleeing as refugees, and almost 8 million internally displaced[1] – Syrians have been responding to and documenting their crisis creatively, taking advantage of greater freedom of expression of an essentially collapsed state (compared to the fierce censorship that reigned during Assad’s unchallenged rule). That is not to say that artists are free from the repercussions of their work – many artists have been forced out of work, threatened, beaten, imprisoned, forced to leave the country or, in some cases, killed[2]. In spite of the danger, and beyond the sounds of shelling and bombardments that try to drown them out, many artists both inside and outside the country continue to battle against tyranny to make their voices, and those of the Syrian people, heard.

‘Bring down Bashar’ graffiti. Courtesy Jan Sefti, https://www.flickr.com/photos/8605011@N02/5614565122

Throwing out the rulebook

Marginal forms of artistic practice are taking on new agency in Syria; the boundary between art, politics and active citizenship is becoming increasingly fluid; and the Internet is providing a platform for expression and dissemination. Popularised art forms include graffiti, community interventions, graphic design, cartoons, comics and puppetry. These forms of visual communication work seamlessly alongside acts of protest and resistance – they are quick, simple and impactful, and carry the message of dissent.

Ali Ferzat is one of Syria’s best-known political cartoonists and has been publishing subtly subversive cartoons for decades in state-run newspapers such as Al Thawra (The Revolution). Since 2011, Ferzat’s cartoons have become less symbolic and more blatant in their derision of the state. A (likely government-organised) attack, in which he was beaten and both of his hands were broken, lead him to flee to Kuwait. He continues to produce images, whilst many more cartoonists and comic artists have risen to prominence. Comic4Syria are a group of artists who publish comics on their Facebook page that respond to the brutality of state-sponsored groups and tell everyday stories of resistance. Their comic strips act as a vent for the frustrations of the local public and offers insight for foreign audiences, for whom they write in English, into the conflict on the ground.

Increasingly, online platforms and social media have played a large role in making such art visible, which, considering the rapidly displaced population and growth of international solidarity, is an important tool for Syrian resistance. Many groups and collectives are using the Internet to disseminate their works and create a virtual community of support. Groups such as the Alshaab alsori aref tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way) collective produce striking posters and banners that can be downloaded and printed from social media sites to be used anywhere in the world[3], and which were employed heavily in protests throughout Syria in 2011. Another initiative, Art and Freedom (arte.liberte.syrie), uses a Facebook page as a symbolic artistic space for solidarity, allowing artists to post their work online in exchange for signing their names to show their support for the revolution.

Satire: dark humour for dark times

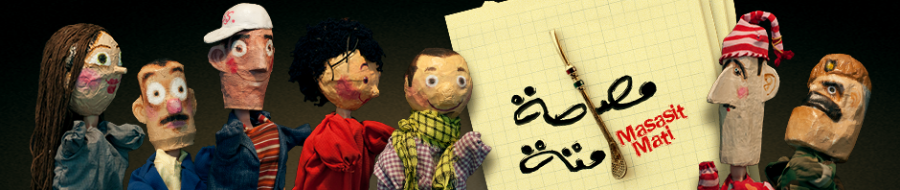

Alongside these artistic forms, satire emerges as one of the central threads running through the art being produced in and about Syria today[4]. Satire and mockery have long been a part of the cultural creativity in the country, as can be seen in the poems and plays of Mohammed Al-Maghout in the 1970s[5] and Ali Ferzat’s early anti-regime cartoons. One anonymous Syrian communication expert argues that the success and potency of satire in art lies in its ability to catch the regime and military off-guard: ‘They know how to play when arms are involved, but do not know how to react to mash-ups, parodies and irony’[6]. For the artists and citizens themselves, such art also acts as a reprise from the horrors and atrocities of daily life and as a space where people can feel a sense of control and autonomy. A member of Masasit Mati also argues that people need to ‘laugh and enjoy things’ in order to exist and that this retained sense of humour by the Syrians ‘shows us their strength and their determination to not just see themselves as victims’[7].

Masasit Mati is an anonymous art collective who use puppetry to ridicule both state and oppositional groups, which has risen to prominence as one of the most internationally popular creative enterprises to come out of the Syrian Revolution. The collective, who use the traditional Syrian art of puppetry, have now released three series of their satirical puppet videos Top Goon and have been viewed by thousands on their Facebook and YouTube sites. In 2013, the group took to the Syrian streets to bring puppetry back to the people, saying that despite the importance of the Internet in their art and message, they don’t want to be disconnected from the public on the ground. Unfortunately, increased shelling and attacks have forced them back into the confines of the digital world.

Satire has also taken on a performative guise in protests that adopt artistic elements. Such interventions include an incident where the seven main fountains of Damascus were dyed red, to represent the state’s killing of thousands of civilians. One of the fountains is located directly in front of Syria’s intelligence service headquarters; the dramatic red water symbolised both the state’s cruelty and their weakness, despite their military power, to prevent such actions.

Red fountains in Damascus. http://www.everydayrebellion.net/blood-fountains-against-the-civil-war-2/

Similarly, activist Ahmed Zaino released hundreds of ping-pong balls featuring the word hurriyah (Arabic for ‘freedom’) into the streets of Damascus, after which security forces helplessly chased, with some balls rolling into the grounds of Bashar al-Assad’s palace[8]. At times when the security forces attempted to prevent such interventions, artists and activists have responded imaginatively – when regime checkpoints prevented people from demonstrating around the infamous Clock Tower Square in Homs, people created their own miniature clock towers and protested around them instead.[9] These acts of creative subversion construct a physical space that the protestors can inhabit as well as highlighting glimmers of state weakness and futility.

The artistic production coming from and about Syria is monumental in all meanings of the word – in quantity, scope, and form but also in courage and resilience. The cultural outpouring since the 2011 revolution has created a legacy that cannot be erased as easily as the bombed-out cities and contested territories of Syria itself. What started as a political revolution has created a cultural revolution of sorts – a space that allows for greater freedom of expression and an urgent and constant topic of inspiration.

–

For more information on the arts and culture of Syria see: Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, eds. Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen and Nawara Mahfoud (London: Saqi Books, 2014).

Aimee Dawson is a London-based writer and blogger on contemporary art from the Middle East and North Africa. She studied Arabic and Middle East Studies at the University of Exeter and spent a year living and studying in Cairo and Fez. She was the writer-in-residence for Shubbak Festival 2015, is a guest blogger for Nour Festival of Arts 2015, is the Editorial Assistant at Ibraaz.org, and the Editorial Intern at The Arts Newspaper. She has recently completed her Masters in Contemporary Art and Art Theory of Asia and Africa at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. @amldawson

[1] ‘Syria’s Artists: Between Freedom and Tyranny’, The Syrian Observer, 24 June 2015, http://syrianobserver.com/EN/Features/29391/Syria_Artists_Between_Freedom_Tyranny

[2] Ibid.

[3] Malu Halasa, ‘Art of Resistance’, Index on Censorship, September 2012, 41:3, pp. 141-152.

[4] Malu Halasa (ed.), Culture in Definance: Continuing Traditions of Satire, Art, and the Struggle for Freedom in Syria (Amsterdam: Prince Claus Fund Gallery, 2012), http://www.princeclausfund.org/files/docs/2012%20Culture%20in%20Defiance.pdf

[5] Eyad N. Al-Samman, ‘Mohammed Ahmed Al-Maghout, the Syrian poet with a satiric pen’, The Yemen Times, 2009 http://www.arabworldbooks.com/Readers2009/articles/maghut_alsamman.htm

[6] Donatella Della Ratta, ‘Irony, Satire, and Humor in the Battle for Syria’, Muftah, 23 February 2012, http://muftah.org/irony-satire-and-humor-in-the-battle-for-syria/#.Vic8XxArJ0t

[7] Aimee Dawson, ‘Holding up a Mirror to the International Community: An Interview with Masasit Mati of Top Goon’, Shubbak Festival blog, 15 July 2015, http://www.shubbak.co.uk/holding-up-a-mirror-to-the-international-community-an-interview-with-massasit-mati-of-top-goon/

[8] ‘Syrian Activist Ahmed Fights With Ping Pong Balls’, Everyday Rebellion, http://www.everydayrebellion.net/tag/ahmed-zaino/

[9] Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, eds. Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen and Nawara Mahfoud (London: Saqi Books, 2014).